The Month In Markets - January 2022

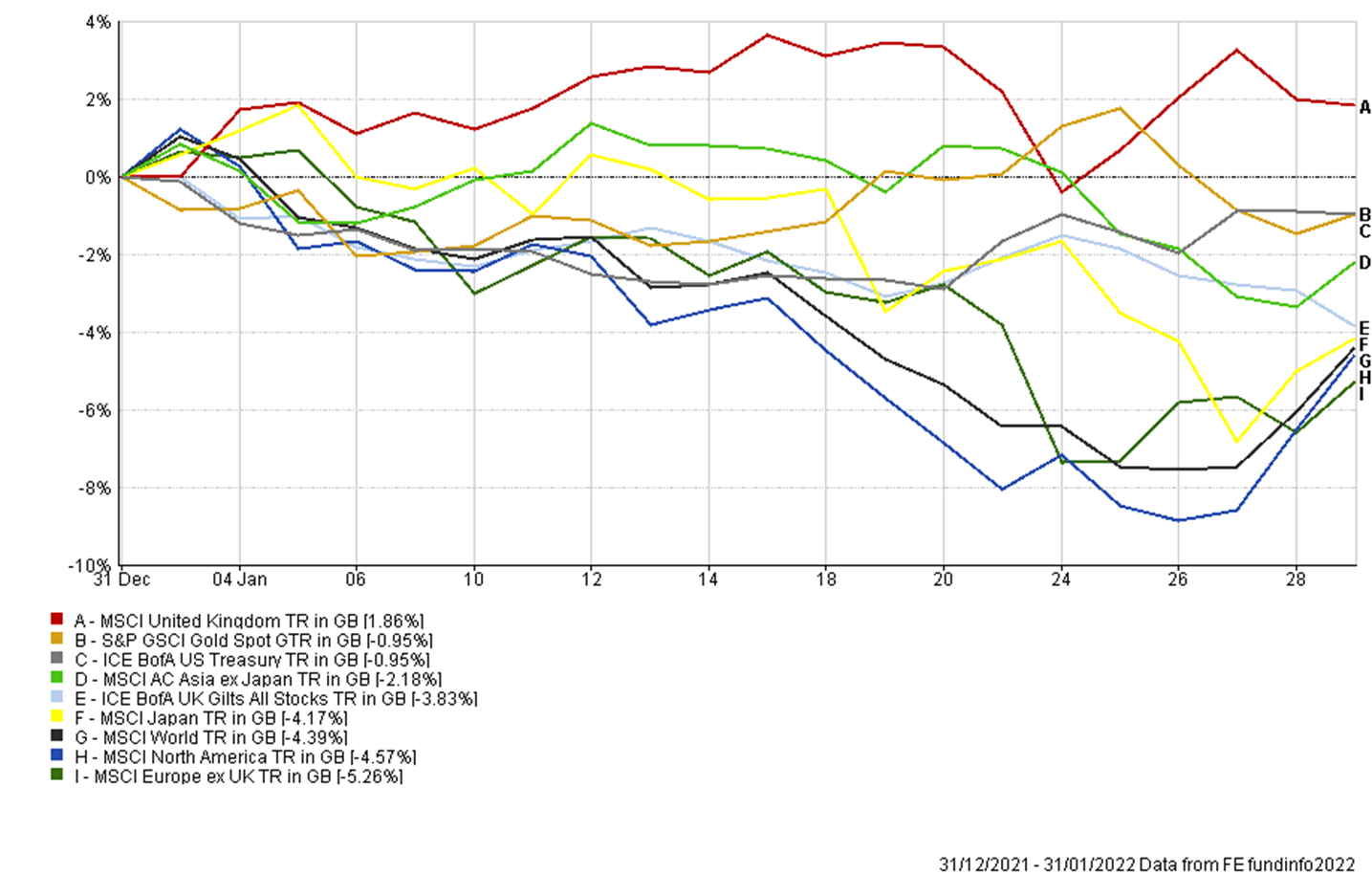

It’s been a white knuckle start to the year. As you can see from the chart, markets have plotted some dramatic courses, with global equities down by almost 8% at one point. But this picture plays down what’s been happening within markets: This is where the month’s real action happened.

We saw similar trends in December, albeit to a lesser degree. You’ll see them described as a ‘market rotation’ in the press. But what does that mean?

We’re used to hearing about stock market sell-offs and rallies, or bear and bull markets. These simply describe whether the market is falling or rising. A rotation refers to a change within the market and doesn’t imply that the whole market is moving in any particular direction. Instead, it means that one part of the market that was winning has started to lose, while another part that was lagging has taken the reins.

You could compare it to politics. The UK has continued to grow over the last 30 years, but every now and then its leadership changed – and not just the prime minister, the entire ideology underwent a seismic shift. Think of the landslide move from Conservatives to New Labour in 1997, or the crumbling of that movement and the return of the Conservatives in 2010.

We see similar shifts within markets too. In fact, when I look back on my career in the investment industry (26 years and counting – where did it all go?) stock markets, like politics, have see-sawed at least twice between different super-tanker themes and ideologies. We may now be experiencing another.

The first, in my career anyway, was the tech bubble of the late 90s. I remember getting caught up in the greed and excitement for the next big money-spinner, I’m just grateful I was only in charge of my own money at the time (of which there wasn’t much and, thankfully, I was too boringly conservative to consider borrowing to speculate).

Then came the rotation. Tech stocks and funds – good or bad – wobbled, collapsed, then flatlined for years. There were a few funds that had steadfastly resisted the urge to go all-in on tech (although many either folded, closed or sacked their managers), and these sailed serenely higher as the tech hoopla deflated. The whole experience made a big impression on me.

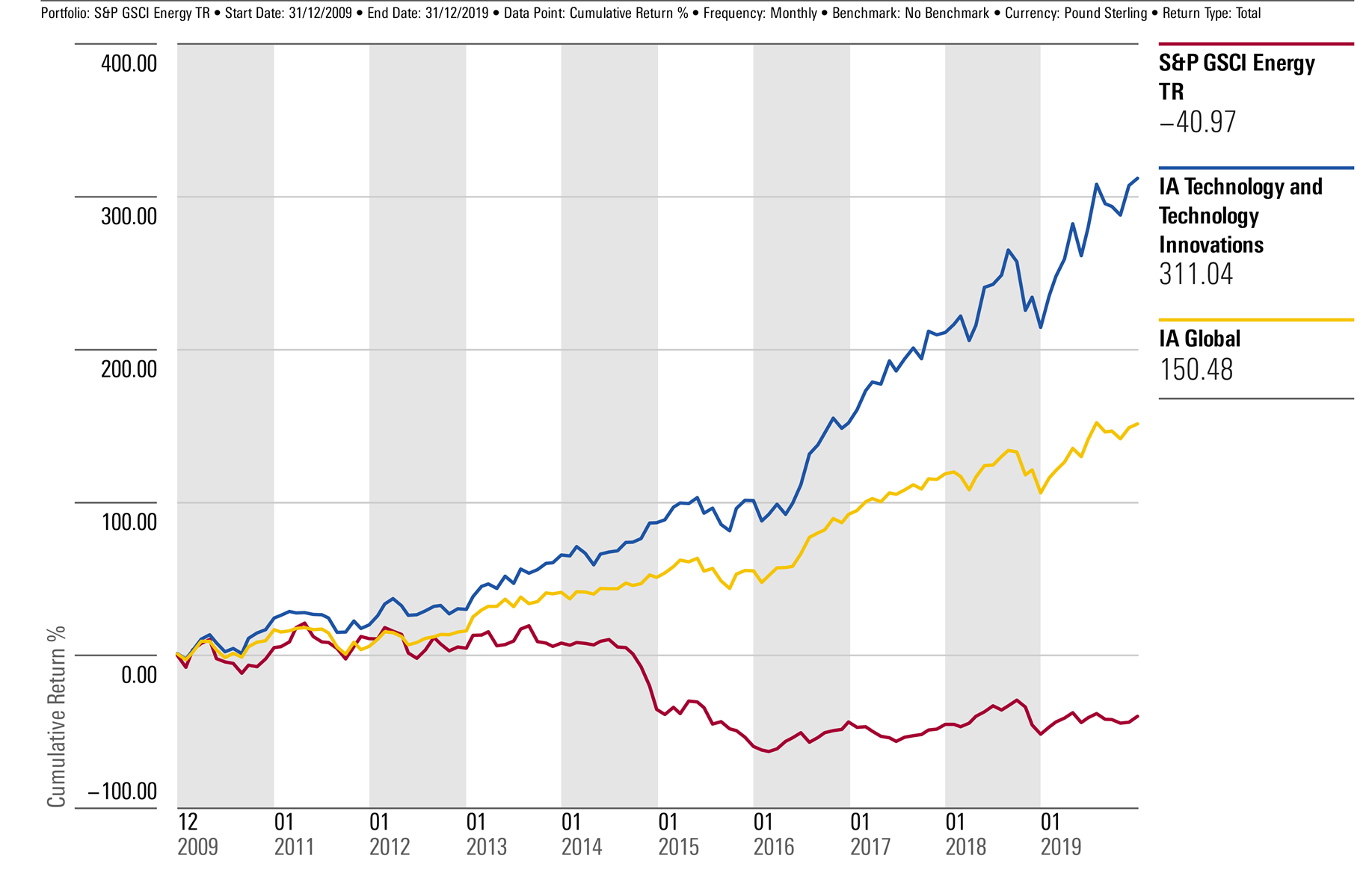

It’s easy to forget now, from our 2022 tech-tinted lenses, but technology stocks and funds became untouchable outcasts in the noughties. Sure; it wasn’t a great ten years for stock markets – the average global equity fund only made 6% – but it was truly dire for the once-mighty tech sector. The average tech fund lost 62% in that time*.

So, by 2010, having talked of nothing else just ten years earlier, very few people even mentioned tech investing, let alone bought technology-focused growth funds (and this is a couple of years after the launch of Apple’s world-changing iPhone). This silence and disinterest, so it turned out, was a fabulous buying opportunity.

The flipside of this trend has been energy and commodities. After a dismal 90s, these captured investors’ attention (and money) in the noughties as tech limped into the background. Now they were viewed as the chief beneficiaries of the era’s sexiest story: They would power the emergence and growth of China.

So as tech funds lost 62%, and the global stock struggled to a measly 6%, energy stocks rose by 90% in the noughties**. This meant that, while tech funds languished at the foot of the decade’s fund performance tables, the top was filled with energy and commodity specialists, or funds invested solely in energy-dominated markets, like Brazil or Russia. And, just as at the peak of the tech frenzy a decade before, investors could think of little else, and shovelled in more money expecting a repeat of the previous ten years’ stellar run.

Then came the rotation. Natural resource stocks and commodity prices wobbled, collapsed, then flatlined for years. While those funds that had resisted the urge to join the party (ironically, in many cases, by picking up unloved technology stocks) sailed serenely higher as the commodity hoopla deflated.

The next ten years painted a mirror image of the experience in the noughties: energy stocks lost 41% in that time, while tech funds wrestled back control of the narrative, producing 311% between 2010 and 2020.

So those are rotations. They’re not common, but they do happen. A changing of the guard that can turn successful strategies into failures overnight.

So are we seeing another regime change now?

Tech stocks, which have been in charge for more than a decade, have been wobbling for a while. But what we saw in January felt a little more like collapse. Most of the severe falls have so far been limited to smaller, more speculative stocks. But even some of the giants began to look vulnerable: Netflix, which put the ‘N’ in the ‘FAANGS’ acronym, fell by more than 28% over the month, having reported disappointing subscriber growth.

At the same time, energy companies fared well. Fuel prices are marching higher, while years of underinvestment mean new supply, which in previous years brought the price back down again, is scarce.

You can see this reflected in the earlier chart. The UK stock market has a large weighting in energy companies and hardly any exposure to tech shares – and it rose while other markets sold off. In contrast, the US has a far larger weighting to tech stocks, and it was walloped.

I’m wary here that I’ve made this sound too simple: If this is a rotation, why don’t we pull all your money out of the last decade’s winners and put it into its laggards?

One reason is because the ‘bait and switch’ of a long trend followed by rotation is just one of the markets’ regular tricks. Another is to present an apparently easy rule for making money (in this case simply switching horses every ten years), then whip it away at the exact point investors have figured it out.

So we shouldn’t be too quick to declare this a permanent rotation. The world is different now to when the tech bubble burst and energy stocks came to favour: Today central bankers seem more interested in keeping stock markets high; many tech firms are now quasi-monopolies, not flighty dotcom start-ups; and we have a far greater focus on using technology to move us permanently away from fossil fuels.

Indeed, as the month drew on, the rotation began to ebb, and fears over a war with Russia over Ukraine began to drive markets instead, dragging everything lower (you can see this on the chart when the UK and Europe start to play catch-down with the US).

This provided a timely reminder that balance is key. Just as we didn’t push all your money into one type of investment last decade, we’re not going to push it all into another for this one either. Diversification may reduce the chances of getting rich quick, but it’s the best way we know to avoid getting poor quickly, and that’s where our priority lies.

Simon Evan-Cook

(On Behalf of Raymond James, Barbican)

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. This article is intended for informational purposes only and no action should be taken or refrained from being taken as a consequence without consulting a suitably qualified and regulated person.