The Month In Markets - July

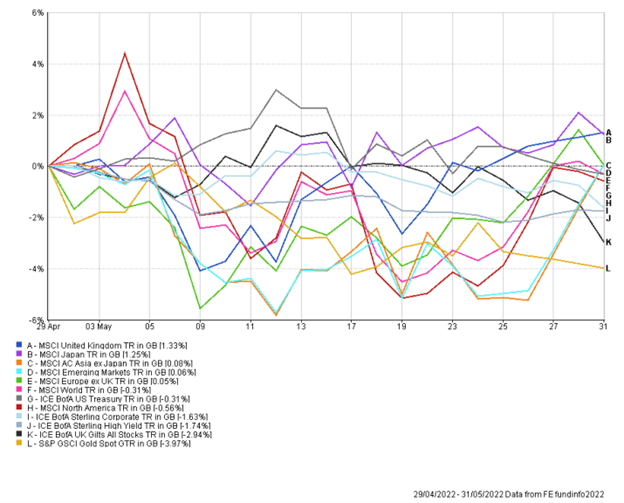

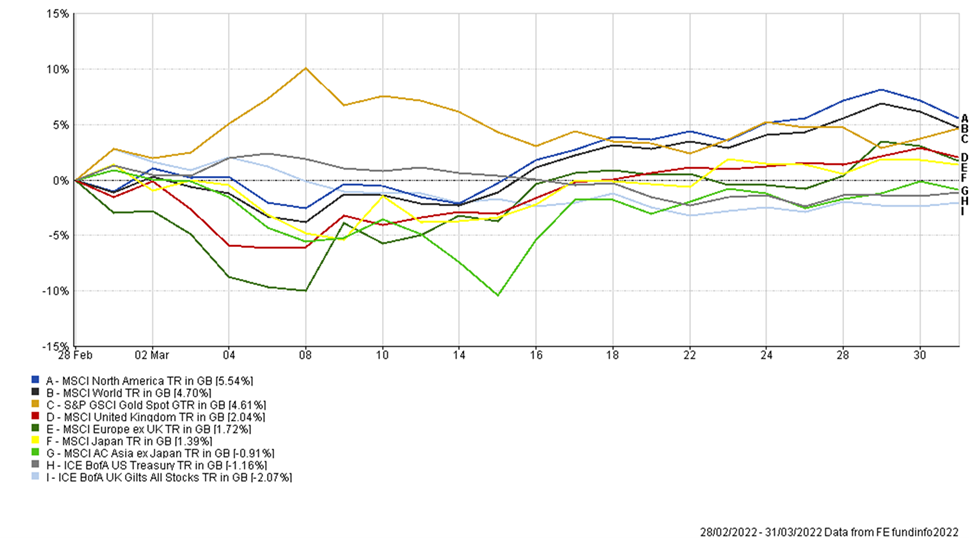

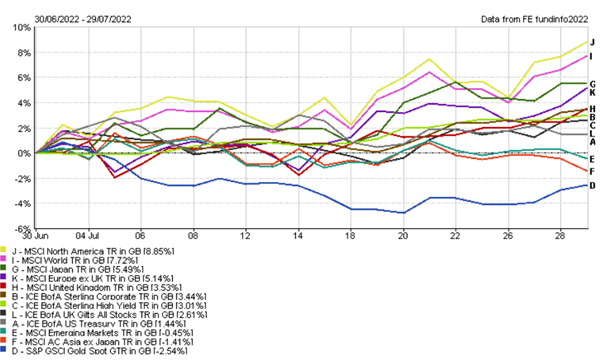

The month of July did not particularly feel like a great month. There was little to no progress with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Inflation data continued to come in at eye-wateringly high levels. Supply woes continued and Google searches for the word “recession” spiked. Yet despite all of this, risk assets in general produced strong positive returns during July.

So why did the price of developed market equities and bonds rise this month? We don’t believe it was caused by an improvement in the short-term economic outlook, given economic data was weak during the month.

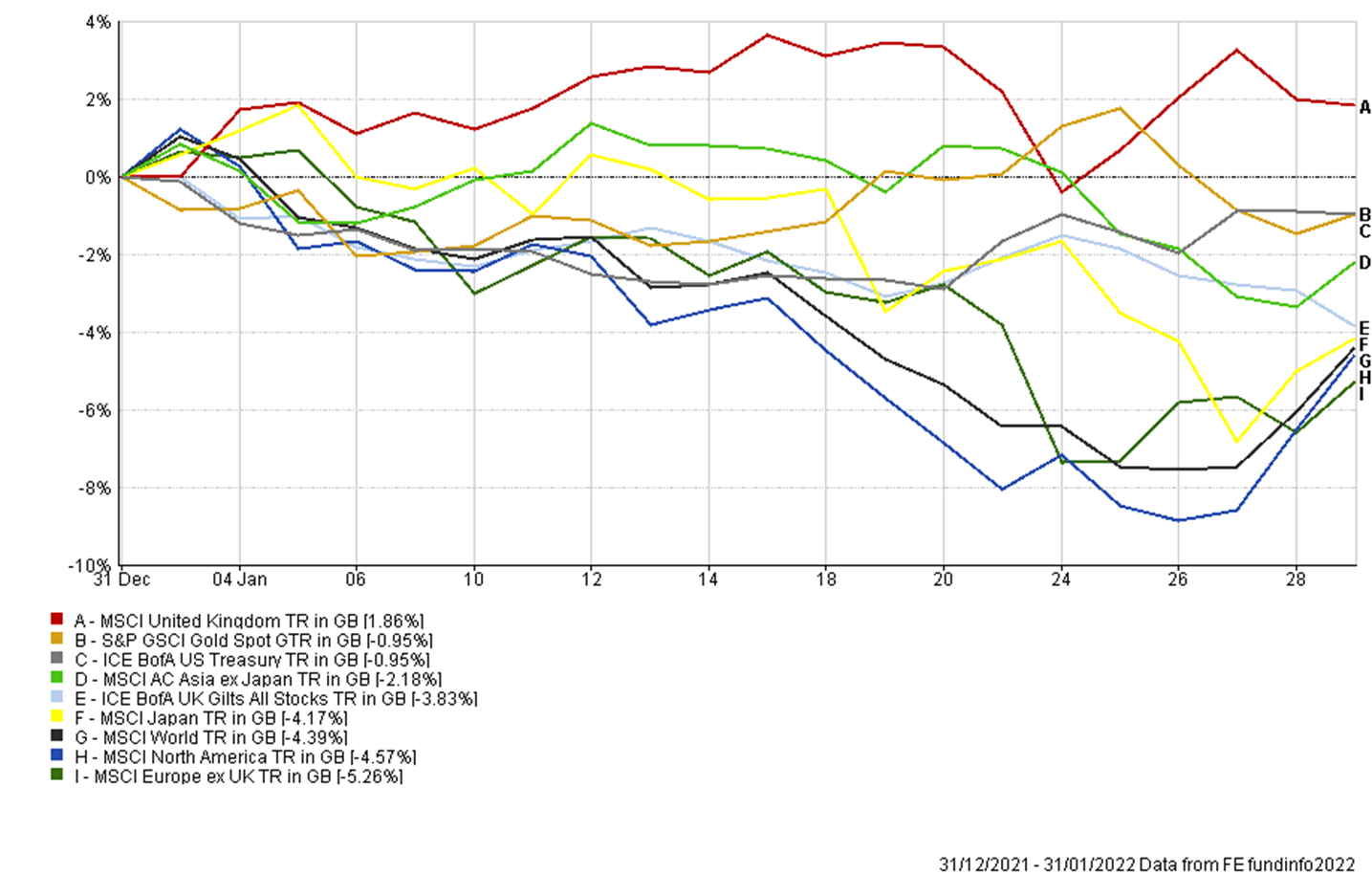

Additionally, it wasn’t because inflation appeared to be peaking. The most recent inflation data reported came in at 9.4% and 9.1% in the UK and the US respectively, reaching fresh 40-year highs. It was interesting to see that bonds and stocks prices increased despite these higher-than-expected inflation rates, as opposed to earlier in the year when these assets declined in value as a result of heightened inflation data.

What then was driving markets, if not positive data? We believe that during this month, investor attention shifted, and asset prices entered a strange state in which bad economic news was embraced. If inflation worries dominated the first half of the year, then concerns about economic growth dominated July.

The market has begun to discount the possibility of central banks having to backtrack on their interest rate hikes, something that is being referred to as the “Fed Pivot”. If the economy shows too many signs of slowing and the risk of recession increases, central banks could be forced to pivot away from the higher interest rate path and either pause or even cut interest rates in order to support the economy. The weak economic data of July fueled investors beliefs that the “Fed pivot” was coming into play. Historically, inflation falls in recessionary environments as demand declines, unemployment rises, and business investment slows.

Thinking at very simplistic levels, if the problems affecting the asset markets this year have been high inflation and rising interest rates, it makes sense that asset prices can rebound if we start to consider a world where inflation could fall, and interest rates won’t reach the lofty heights that were previously expected.

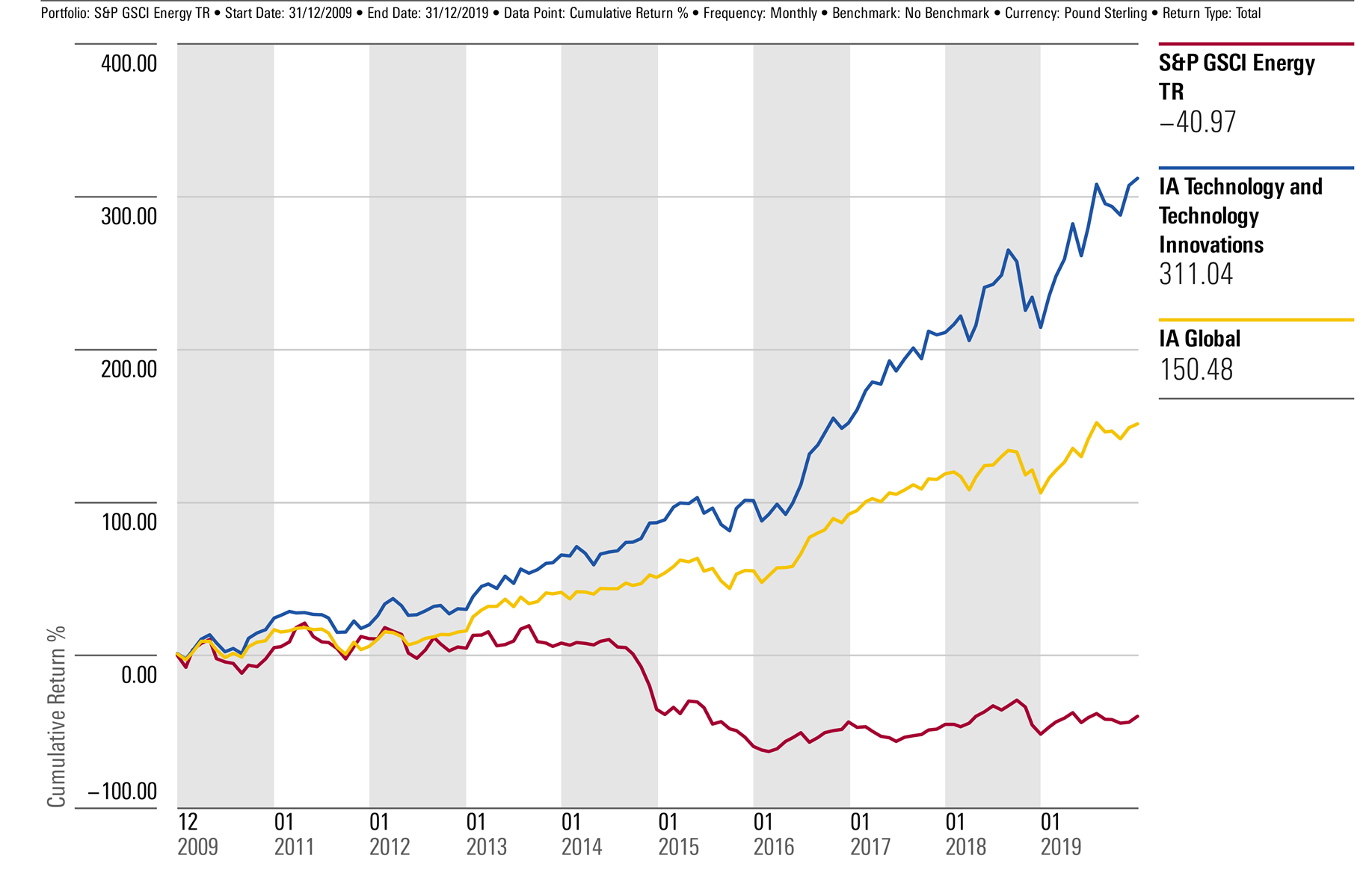

We can draw parallels from the final quarter of 2018, leading into 2019. Although inflation was muted then, the US central bank was embarking on the final leg of their interest rate hiking cycle. Quarter 4 of 2018 and the month of December were very tricky for equity markets, as they begun to price in a higher interest rate environment. However, by the end of the year, economic data had deteriorated, and the market determined that rates would not reach the previously priced in levels and in fact the US Fed would pivot and begin to ease monetary policy. This is what occurred; the US Fed never raised rates in 2019 and instead cut rates later in the year. In terms of asset prices, we saw equities and bonds perform very well in 2019 as valuations for equities increased (due to lower rates) and bond yields declined (prices rose). While we aren’t categorically saying it will happen again, it is always useful to study similar periods in history and take both downside and upside risk into account.

The old adage of “buy low, sell high” may have also been in play in July. The first six months of the year have been extremely challenging with steep declines in bonds and equities. There will be some long-term investors deploying cash at these levels. Large parts of the bond universe are offering yields that we haven’t seen for a decade. There are risks associated with this, but we know starting yield is a good predictor of future returns. Likewise, equity valuations have contracted this year and for investors who believe the price you pay matters and impacts future returns, July provided an attractive long-term entry point.

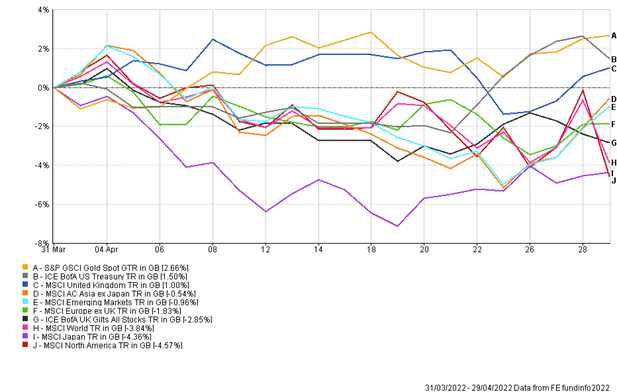

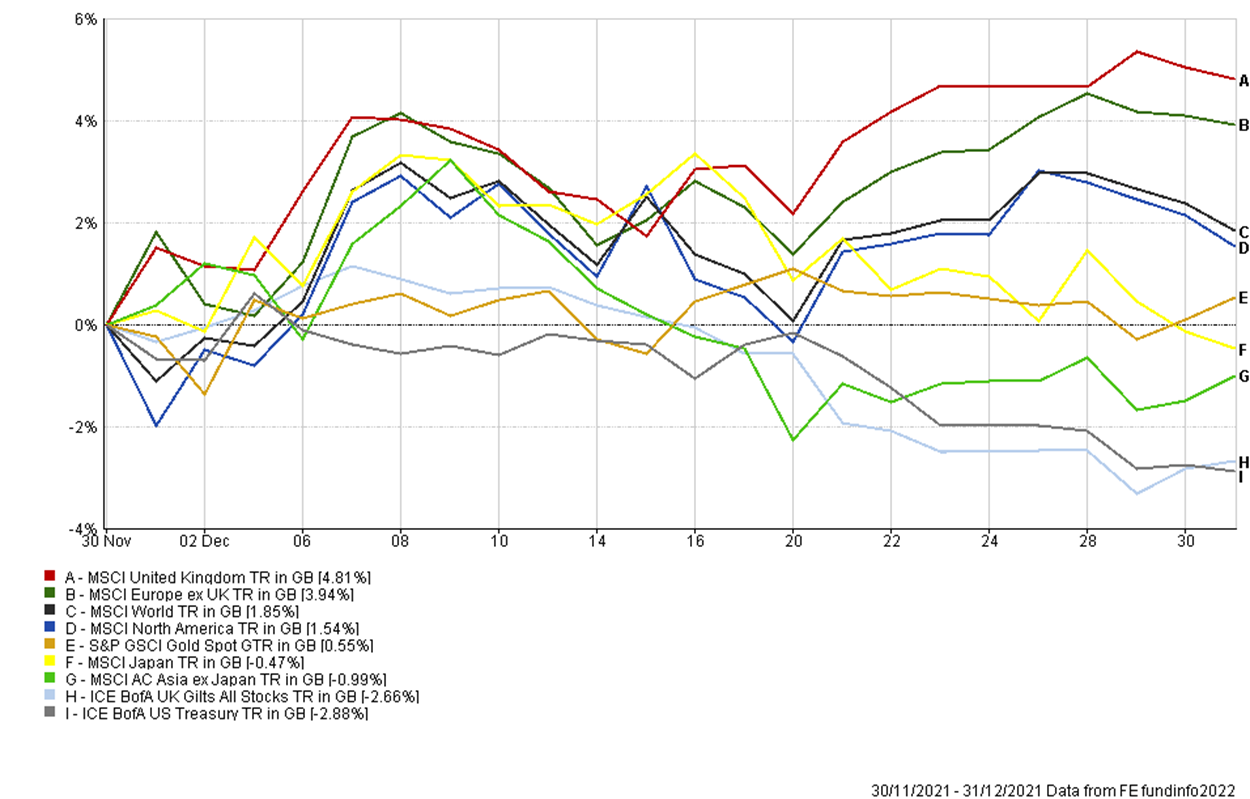

You will notice from the monthly chart that Asia ex-Japan and Emerging Markets equities lagged their developed counterparts. One of the biggest drivers of this was weakness in China, which is the biggest country exposure in most Asian and Emerging market benchmarks. Over the month there were renewed lockdowns as COVID-19 cases were detected and China implemented its Covid-zero policy. This rattled markets, while it has also taken its toll on the population, with dissent rising in the country. The Chinese real estate market was also under pressure in July, with reports from S&P Global Ratings that property sales could fall 28%-33% in 2022.

In times of heightened volatility investors are often more susceptible to behavioural biases. It’s likely many investors wanted to run for the hills and sell to cash after such a difficult June. However, in doing so, they would have missed out on an exceptionally strong month of July. No doubt these investors are now wrestling with the difficult decision of whether to invest at much higher levels than four weeks ago.

While we believe in active management and making tactical changes to portfolios, it is very rare that we make big sweeping portfolio changes. This is a very purposeful approach, and is a process designed to remove (or at least limit) our own emotions getting in the way and leading to sub-optimal decisions.

Andy Triggs

Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Appendix

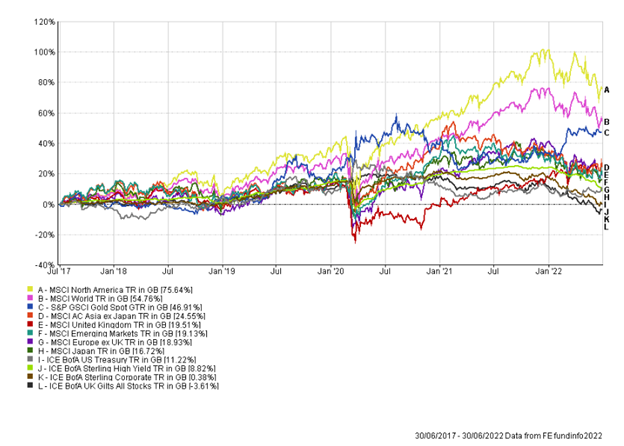

5-year performance chart

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. This article is intended for informational purposes only and no action should be taken or refrained from being taken as a consequence without consulting a suitably qualified and regulated person.