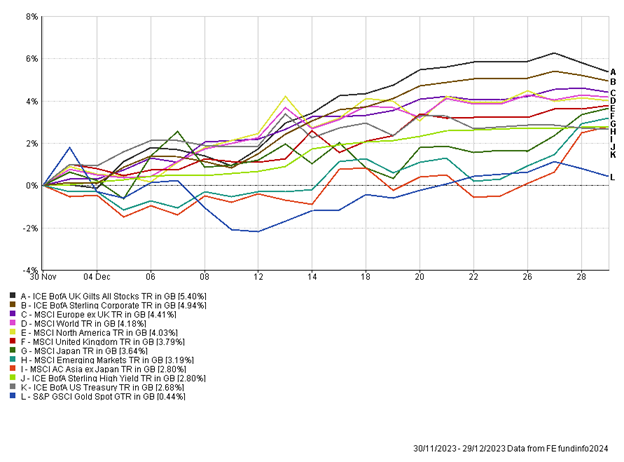

The Month In Markets - February 2024

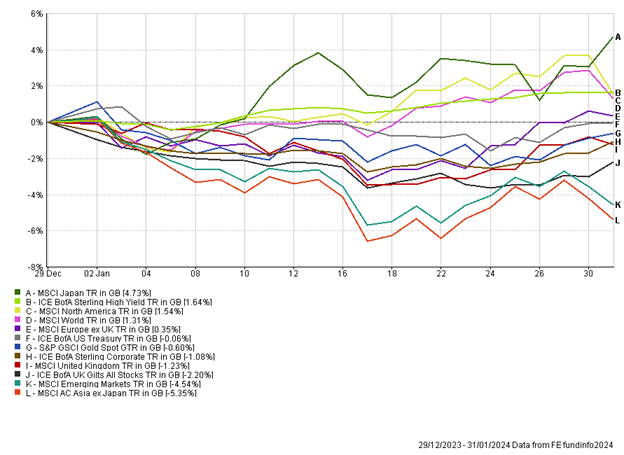

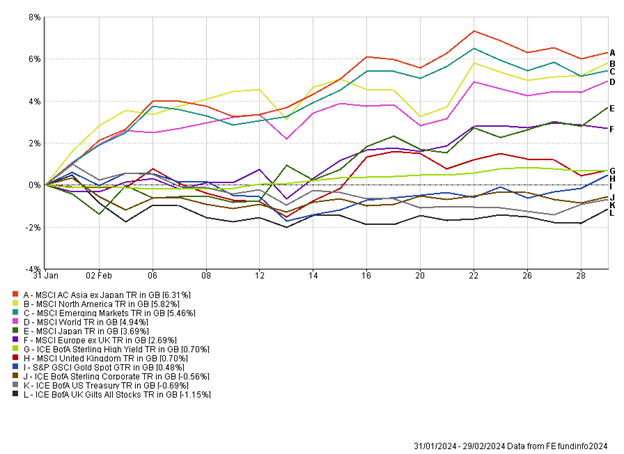

February was a strong month for equity investors, led by last month’s laggard in Asia ex Japan equities. Fixed income assets remained under pressure and did not participate in the equity rally.

Over recent months we have written about weakness in the Chinese equity market, which has dragged down Asian and emerging market indices. There was a strong rebound this month as Chinese equities rallied around 10% in sterling terms. Given China is the largest weight in most Asian and emerging markets it helped propel these indices higher. It appears the market is starting to believe that Chinese policymakers are determined to end the equity market rout, while there are early signs of improving economic and earnings data. Only time will tell if the rally will be sustained, but foreign flows back into China have ticked up.

The continued story driving the US equity market centered around artificial intelligence (AI), with Nvidia continuing its exceptional share price rally. The company released quarterly results mid-way through the month, and it once again beat revenue and earnings expectations, leading to strong gains. The shares rose 16% on the news, adding an astonishing $272bn (£219bn) in market cap in a single day. To put this into perspective the largest UK-listed company is AstraZeneca, which has a market cap of around £165bn. The staggering moves have led to Nvidia’s market cap breaching $2 trillion. At an index level, the US market has appeared very strong both in February and for the last 12 months or so. However, that performance has largely come from a handful of stocks, labelled the “Magnificent Seven”. Many other parts of the US market have actually struggled over the short-term and have been overlooked, with investors instead focusing on the alluring narrative surrounding AI. This can create opportunities, with unloved stocks, which have strong fundamentals, offering good long-term potential. As investors who focus on both valuation and diversification, we are naturally drawn to these parts of the market, while also allocating to the mega-cap names through passive vehicles and a technology focused fund.

UK equities were a laggard during the month. There was the headline grabbing news that the UK fell into recession in the second half of 2023. However, the latest economic data indicates that the economy will quickly exit recession and it will have been an extremely mild contraction. While the word “recession” can spook investors, history has shown that UK equities typically perform very strongly over the following 12 months after the start of a technical recession. While this may sound counterintuitive it is worth remembering stock markets are forward looking discounting mechanisms, considering the future environment for companies as opposed to the immediate state of play in economies.

Fixed-income markets remained under pressure during February. The main reason for this was the shifting expectations around when the first-rate cuts will begin. Heading into 2024 the market expected US, UK and European rate cuts to kick off in the month of March. However, a raft of positive economic data and sticky inflation has led to those expectations being kicked down the road, to late Q2 for the first-rate cuts. This led to modest rises in bond yields, negatively impacting prices.

Outside of markets there were developments in the US where it now appears likely that it will once again be Biden vs Trump in the race to the White House. It looks like a very close race, however with over six months to go there is the potential for change. There are key elections in many countries this year, including the UK.

At a portfolio level, there were small changes made within the fixed income exposure, reducing exposure to US government bonds in favour of exposure to UK and global bonds. While the UK has been perceived to be an outlier in terms of inflation relative to its developed peers, there is every possibility that UK inflation will soon be below US inflation and potentially at, or below, the 2% target in Q2. This could provide support for both UK equities and bonds and as such a modest increase in exposure felt prudent. We do continue to be mindful about our overall interest rate sensitivity and many of the government and corporate bonds we hold are focused on short-dated holdings, which tend to exhibit less interest rate sensitivity and less volatility. It has been a strategy that has served us well since 2022 and we continue to favour the front end of the curve, while selectively adding longer-dated bonds to provide some portfolio hedging.

Andy Triggs

Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. This article is intended for informational purposes only and no action should be taken or refrained from being taken as a consequence without consulting a suitably qualified and regulated person.

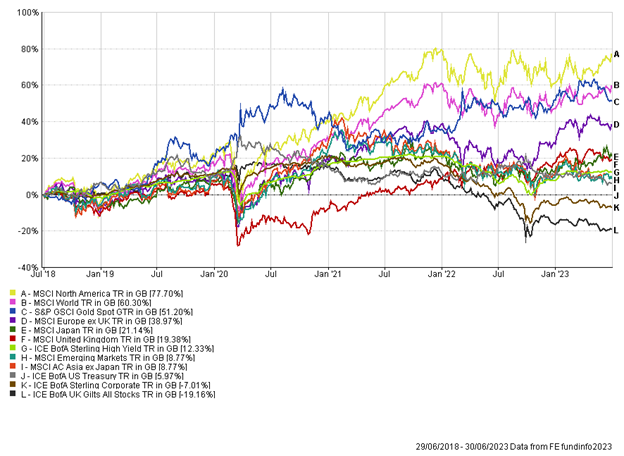

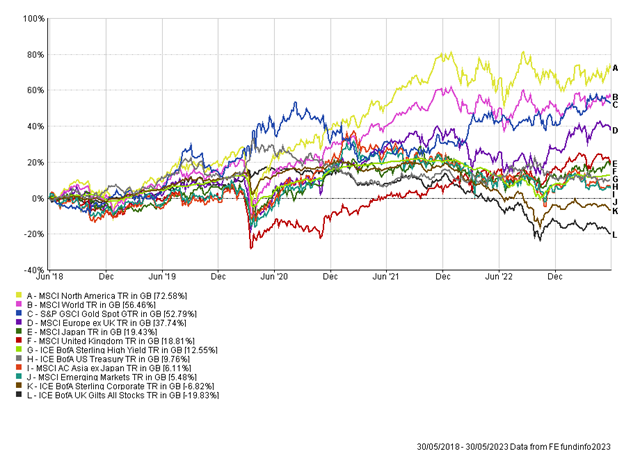

Appendix

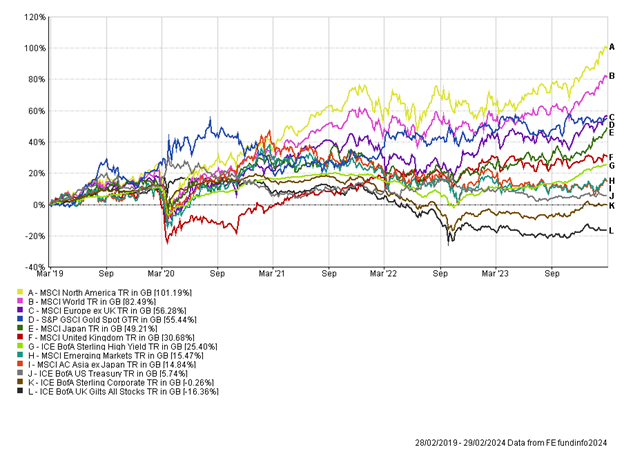

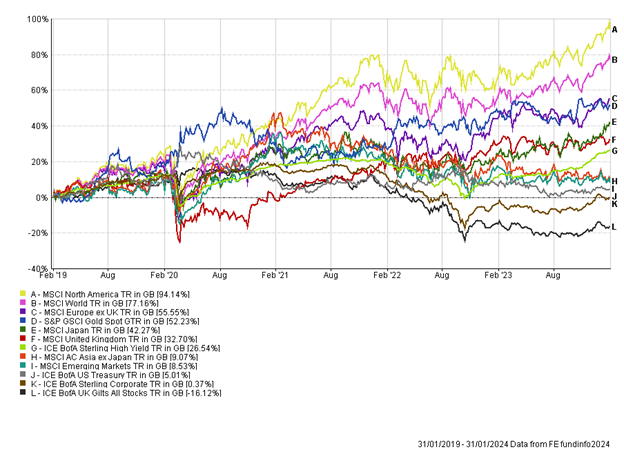

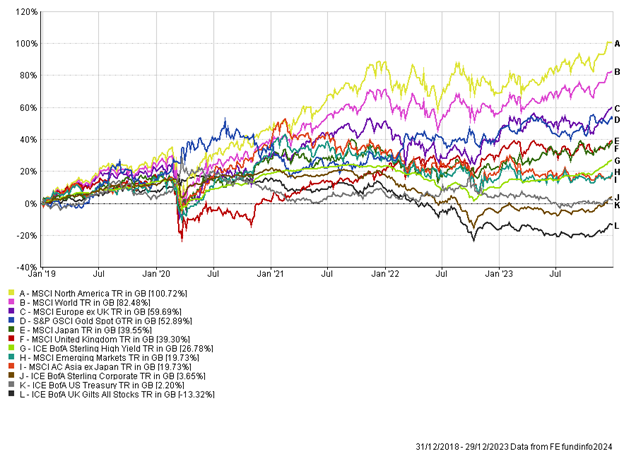

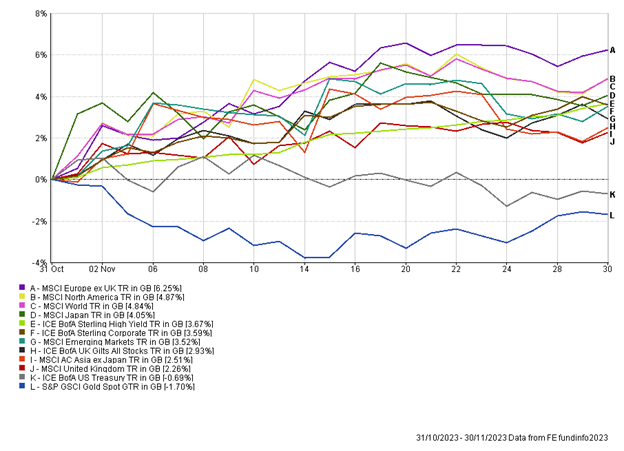

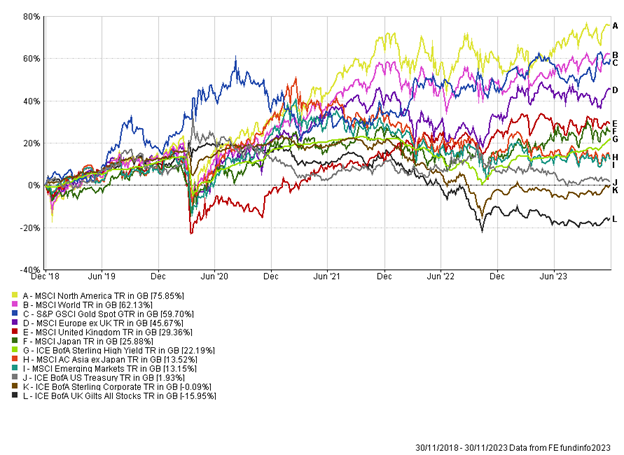

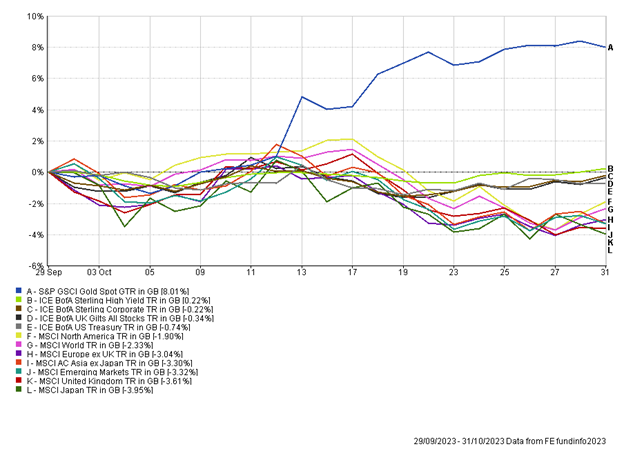

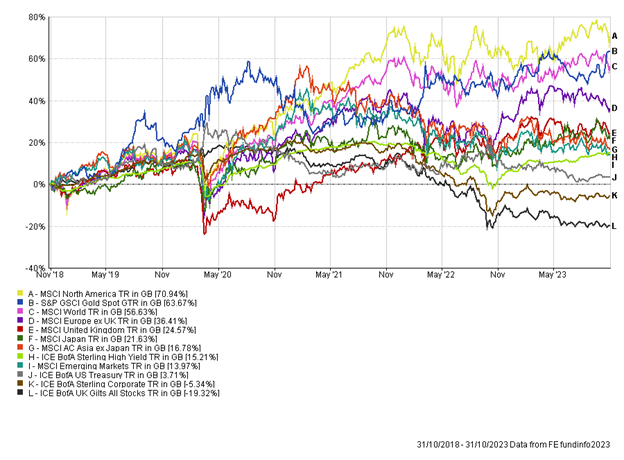

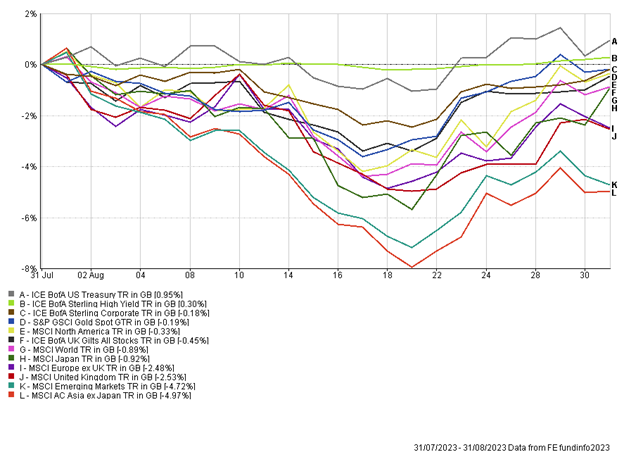

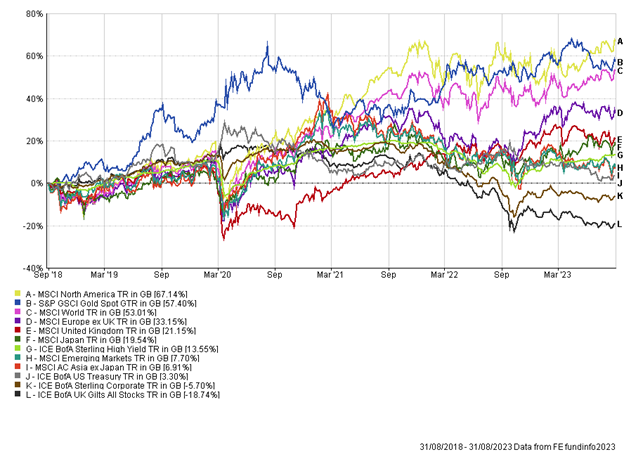

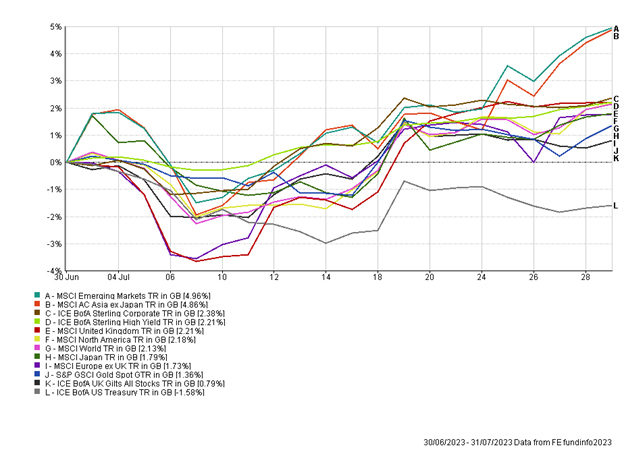

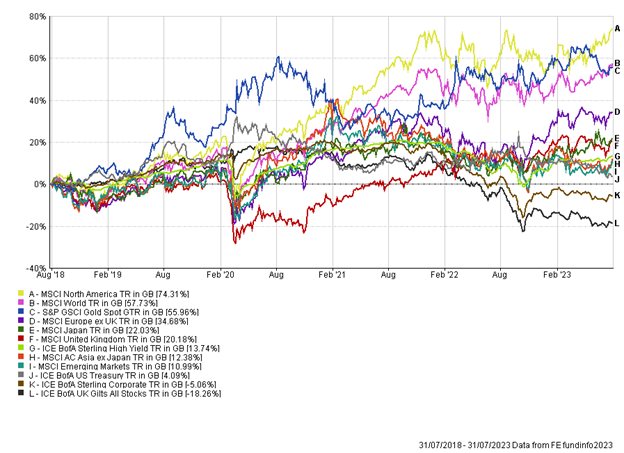

5-year performance chart