It has been 60 years since the Beatles signed their first record deal. The rock group from Liverpool dominated the industry for nearly a decade – and long after that as individual performers. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr created timeless tunes and memorable messages that we can borrow today to portray our economic and financial market outlook.

The Month In Markets – March

The Month In Markets - March 2022

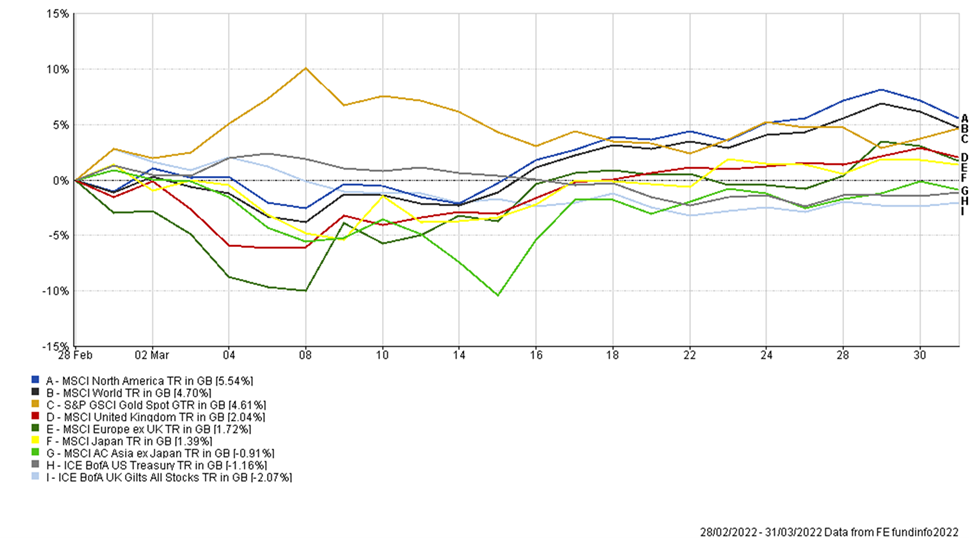

Given what’s happening in the world today, you’d be forgiven for wanting to read this month’s market rundown from behind the sofa. But, true to their history, markets have marched to their own beat again: Despite the depressing backdrop, global equities made a positive return of almost 5% in March, while gilts, which are typically billed as safe havens that perform well in times of stress, fell by more than 2%.

This apparent disconnect is something we’ve touched on a few times already. At the risk of repeating ourselves, markets tend to react to investors’ perception of future events, while – genuine out-of-the-blue shocks aside – often not appearing fussed by what’s in today’s newspaper.

On this basis, maybe what we’ve seen this month is good news: Markets tend to be better at working out what’s actually going on in the world than any one individual (a phenomenon well described in James Surowiecki’s “The Wisdom of Crowds” – worth a read if you’re interested in this type of thing). The fact that they’ve rallied suggests the situation in Ukraine may be improving, at least by more than the relentlessly upsetting newsflow suggests, anyway.

But note that I’ve caveated that statement with words like “suggests” and “may”. We investors like to pepper our reports with terms like this; if we later turn out to be wrong (which we often do), we can always point to these couched terms as a get-out. And it’s right to do that here: Markets have a good record of predicting events before they make the news, but they’re very far from perfect at it. The world is always unpredictable, often taking turns that wrongfoot even “wise” markets.

This is one reason we don’t tamper with your portfolios on a daily basis. Like a defender facing a mazy Jack Grealish run*, you can end up being sent one way, then another, then back again, and ultimately end up on your backside, wondering what just happened.

Instead of chasing our tails by trying to “time” markets, we expend most of our mental energy finding good managers, each an expert in their own corner of the market, to run your money. That way, when times turn hard, they are well prepared for the unexpected. And so, as a consequence, are you.

We’ve had calls with many of the managers running pockets of your money over the last few weeks, and have been reassured by their confidence in their own portfolios (and that, in many cases, they were seizing the opportunity to invest more of their own personal money into their funds).

Outside of your portfolios, meanwhile, there are a fair few fund managers looking dazed and confused right now: As March began, the unsettling events in Ukraine pulled equity markets lower, particularly as the word “nuclear” began to crop up in the conversation.

This caused some to sell some of their equities. But, as you can see from the chart above, since that early-March low point, global equities have rebounded by almost 9%. So, as we stand, their snap decision to sell was a costly mistake.

Of course, it may still turn out to be the right decision. There’s nothing to say events can’t take a darker turn from here, taking markets lower with them. But, for now, the pressure will be on those who sold: Do they stick to their original decision and wait for a fall? Or buy back in at higher prices in case markets keep rising? And if they do buy back in, and markets then crash? Ouch. The whole process can take on a Basil Fawltyesque tone, desperately trying to correct one mistake after another, all the while digging themselves deeper into a hole.

Away from the Ukrainian tragedy, the month also saw a renewed focus on one of our other regular talking points of the last few months: Rising inflation and interest rates. Inflation numbers have continued to come in higher than experts were expecting. The situation in Ukraine and Russia has only added to this, disrupting energy and food supplies, exacerbating what was already a delicate situation on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Central banks, meanwhile, carried on raising rates during the month, with the Bank of England taking the Base Rate to 0.75%, and the US Federal Reserve finally entering the fray with its first quarter-point hike since 2018.

This has kept the downward pressure on government bond prices. Save for a brief interlude after the Ukraine invasion, these assets have had a terrible 2022 so far. UK gilts, which are usually held for defensive purposes, have fallen by more than 7% this year – illustrating how inflation really is their Achilles heel.

That said, and returning to the earlier thoughts about the Wisdom of Crowds, the last week of March did see “growth” equities rally hard (faster-growing businesses, most closely associated with tech firms of late). These parts of the stock market don’t typically respond well to inflation, and had endured a poor year up until last week. But do they know something we don’t? Could it be that, while inflation feels like it’s back with a vengeance, markets have sniffed out an end to the current surge, and a return to the lower-inflation conditions we saw for most of the last decade?

It’s impossible to say, particularly as other markets – government bonds – are simultaneously suggesting the opposite. So we continue to make sure your portfolios aren’t betting on one outcome over the other. Instead we remain, as before, positioned so that either outcome shouldn’t prove damaging to you in the long run.

*Jack Grealish is a fan favourite in the Manchester City and England football teams. For readers of different vintages and affiliations, you can replace his name with, among others, Cristiano Ronaldo, David Ginola, Paul Gascoigne, Maradona or George Best.

Simon Evan-Cook

(On Behalf of Raymond James, Barbican)

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. This article is intended for informational purposes only and no action should be taken or refrained from being taken as a consequence without consulting a suitably qualified and regulated person

The Week In Markets – 26th March – 1st April

Today marks the start of April and with it many will be playing pranks on their friends and relatives in reference to April Fools Day. Looking back over this past week, rampant European inflation data has left the European Central Bank (ECB) looking rather foolish.

German inflation came in at 7.6% this week and Spanish inflation surprised at 9.8%, a multi-decade high. So far, the ECB has been behind the curve with regards to inflation, but this week’s data is going to put more pressure on them to act and raise interest rates in an effort to curb inflation. The bond market reaction this week has begun to price in a shifting in ECB policy with bond yields rising across the board. The yield on the 2-year German bund turned positive for the first time since 2014 while the 10-year yield on Italian government bonds is now through 2%. One of the contributors to inflation is the war in Ukraine, which has pushed commodity prices higher. The war has also had the effect of knocking consumer and business confidence which will cause growth to slow. On Wednesday ECB President Lagarde acknowledged these headwinds during a speech and stated the longer the war persists the higher the economic costs would likely be.

Russia-Ukraine peace talks took place in Turkey this week. Initial hopes of progress led to equity markets rallying, although towards the end of the week there was little sign of any meaningful progress on the ground and equities gave up some of the recent gains. Despite this, global equities have rallied strongly over the last three weeks, recovering a significant portion of year-to-date losses. The US equity market has been a bright spot during March, in part due to its distance from the conflict and limited reliance on Russia for energy needs. Apple, the largest share in the S&P 500 rose on Tuesday for the 11th consecutive trading day, the share’s longest winning streak since 2003 and took the market capitalisation of the company close to $3 trillion. Tesla announced a stock-split on Monday and on the back of the news the shares rallied around 8%, adding roughly the value of Volkswagen to Tesla’s market cap.

Putin’s demands that payments for Russian gas from ‘unfriendly’ nations be made in Roubles led to significant volatility in European gas prices. On Thursday morning there were reports that Putin would accept Euros, but then later in the day stories broke that Putin once again demanded payments in Roubles. The gas price fluctuated by a massive 18% at times during Thursday.

It felt like déjà vu in the UK, with a Canadian company approaching a UK business for the second week in a row. After Brookfield’s rumoured pursuit of Homeserve, the market was made aware of Royal Bank of Canada’s £1.6 billion offer for Brewin Dolphin. The news propelled Brewin Dolphin’s share price over 60% on Thursday morning and once again highlights the value foreign entities are seeing in UK listed businesses. Staying with the UK, housing data continued to be very strong, with house prices rising on average by 14.3% year-on-year, the fastest rate in 17 years.

As is customary for the first Friday of the month, US Non-Farm Payroll data is released. The figure showed 431,000 jobs had been added to the economy, highlighting the continued strength in the labour market. Unemployment fell to 3.6%, while average hourly earnings came in ahead of consensus at 5.6%. The underlying strength of the US jobs market is likely to encourage the US Fed to continue on their tightening path.

The first quarter of 2022 has been a challenging one for investors with a wide range of asset classes falling over the period, driven by big shifts in interest rate rise expectations and latterly the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Despite these headwinds, it’s been pleasing to see portfolios rebounding from the lows in early March. We continue to believe that diversification in asset class and style will be important when trying to navigate more volatile conditions. Some of the best performing holdings in portfolios this quarter have been gold and infrastructure, two asset classes that wouldn’t typically be found in a traditional bond/equity multi-asset portfolio. We will continue to do the hard work and consider a wide range of asset classes to dampen portfolio volatility and capture investment opportunities, that going forward, could look a little different to the past.

Andy Triggs | Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors.

The Spring Statement: The Detail Behind The Headlines

If a week is a long time in politics, then the near five months since Rishi Sunak’s second 2021 Budget feels close to a lifetime. Back on 27 October, it looked like 2022 would be a year of recovery in which the pandemic faded in the rear-view mirror and ‘transitory’ inflation duly transited to lower levels. It has not worked out like that.

The Week In Markets – 19th March – 25th March

It has been a while since we covered the UK in detail in a weekly note, but with inflation data, the Spring Statement and retail sales data all being delivered this week, the UK deserves some bandwidth.

The Spring Statement took centre stage on Wednesday, and the pressure on Rishi Sunak increased with the release of inflation data on Wednesday morning, which came in at 6.2%, the highest level in 30 years and ahead of expectations of 5.9%. The Spring Statement, in truth, did not provide too many surprises and the immediate effect on UK markets was muted. At an economic level, growth was downgraded from 6% for 2022 to 3.8%. While this growth level is still above trend, the impacts of inflation and Russia-Ukraine are expected to negatively impact growth. Data on Friday highlighted that the UK consumer may already be feeling the effect of higher prices, with retail sales falling 0.3% month-on-month and consumer confidence falling to the lowest levels since November 2020. We’ve frequently highlighted that UK equities have traded on a discount to their developed peers since 2016 (Brexit) and one likely outcome of this would be increased M&A activity. After lots of corporate activity last year, we saw Brookfield, a Canadian asset manager emerge as a potential bidder for Homeserve this week. Homeserve shares rose around 15% on the speculation.

European Composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which is seen as a useful measurement of economic health, slipped slightly from the previous month, however, was still above expectations and showed the area was still in expansion territory. Digging a little deeper into the data, it appeared that supply issues continued to deteriorate, which could impact future European growth.

The US economy delivered mixed messages this week. Services and Manufacturing PMIs rebounded from last month and came in well ahead of expectations, however this was offset by declining durable goods orders and US business investment falling for the first time in a year. The data potentially highlights that the US economy may be slowing, which could lead investors to question whether the US Fed can be as aggressive in their planned interest rate hikes.

Unfortunately, there appeared little advance in any peace talks between Russia and Ukraine this week with the conflict continuing, deepening the humanitarian crisis. US President Biden was in Europe this week for talks with allies, and said that Nato would respond if Russia escalated to using chemical weapons in Ukraine. The West also promised more aid for Ukraine and increased sanctions on Russia once again, but stopped short of sanctioning Russian gas supplies into Europe. Many European nations rely heavily on Russian gas and the Belgian Prime Minister this week summed up the difficulties they are facing by saying “We are not at war with ourselves. Sanctions must always have a much bigger impact on the Russian side than on ours”.

Equity markets have in general continued to advance this week, despite what feels like an uneasy economic backdrop. At a stock level Apple recorded its eighth consecutive day of rising on Thursday as the tech heavy Nasdaq index rose nearly 2%. The S&P 500 has advanced in six of the last eight trading days as investors have begun to buy the dip following the sharp declines in markets earlier in the year. The recent success in equities has not spilt over into bond markets however, with developed government bond yields continuing to push higher this week. Continued hawkish language from the US Fed has led the market to now price in an additional 7 rate hikes (of 0.25%) for 2022.

Despite the sell-off in government bond yields, we continue to see merits in maintaining small allocations in portfolios for diversification benefits. Our view is that if we are to enter choppy waters ahead, these assets have the potential to perform well, and would likely offset some of the volatility we would see in equity markets. At some point we may even consider adding to these positions if prices continue to fall, as we are in effect buying portfolio insurance at a cheaper price, with a higher potential future payoff.

Andy Triggs | Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors.

The Week In Markets – 12th March – 18th March

There are times when content for the weekly note can be hard to find. There are other times when the challenge seems to be finding a way to squeeze in all the key points into just a few short paragraphs that can be easily digested on a Friday afternoon. This is definitely one of those busy weeks with subjects such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, US and UK interest rate rises and China’s market intervention all needing to be discussed.

While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has continued, with strikes seemingly intensifying, there have been reports of a softening stance towards negotiations and the hope is that some sort of agreement can be reached in the near-term. These rumours of a potential agreement supported European equities, with the Euro Stoxx index up nearly 5% over the course of the week. UK markets were also once again strong this week, with the more domestically focused FTSE 250 index rising around 3.5% since Monday. The oil price has remained volatile throughout the week, at one point falling below $100 a barrel, but rising again on Thursday and Friday.

The US Fed raised interest rates for the first time since 2018, nudging base rates up by 0.25% to 0.5%. Given the recent strength of the US economy, coupled with inflation running at 7.9% currently, it’s staggering to believe policy has been so accommodative. The market, and indeed US Fed, believe they will need to continue to raise rates throughout the year in an effort to combat inflation and excess growth. However, economists have this week downgraded US growth expectations for 2022 and there is a risk of policy error here; that the US Fed raise interest rates too quickly into what is a slowing economy. On the back of the rate hike and hawkish language from Fed chair Powell US government bond yields rose, with the 10-year treasury hitting 2.2%, a post-COVID high. The Bank of England (BoE) followed suit on Thursday, increasing UK interest rates from 0.5% to 0.75%. The BoE struck a much more dovish tone, acknowledging that inflation is likely to be higher in the short-term due to the invasion of Ukraine, but that higher energy prices would be a drag on growth to net energy importing countries, such as the UK. The expectation now is the BoE may be slightly more cautious in raising rates going forward.

Chinese equities came under intense selling pressure early in the week as investors questioned whether China’s links to Russia could lead to Chinese sanctions. This was on top of concerns around regulation and the Chinese property market and was enough to trigger Beijing to intervene. The state council vowed to keep capital markets stable, support overseas stock listings, handle risks for property developers and said regulation for the technology sector would soon end. The news sent Chinese stocks higher, with the Hang Seng Tech Index up an incredible 14% on Wednesday. China and US tensions continue to be a little strained, so all eyes will be on the call between US President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jingping later this afternoon, the first time the two will have spoken since Russia’s invasion.

What appears like a challenging week has actually been positive for global equities, with most major indices advancing throughout the week, and this has fed through to our portfolios. Bond markets have remained challenged with inflationary pressures negatively impacting prices.

Next week’s note is likely to be a busy one once again; Rishi Sunak is due to deliver the Spring Statement on Wednesday, with energy prices and the National Insurance increase in focus. At a portfolio level we will try to assess the longer-term implications of any announcements, instead of trying to make short-term bets, which are often driven by luck as opposed to skill and notoriously hard to get right consistently.

Andy Triggs | Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors.

The Week In Markets – 5 March – 11 March

The last seven days have felt like a rollercoaster in markets with big daily moves in asset prices and volatility remaining high throughout the week. The constant newsflow and short-term noise can prove slightly overwhelming at times like this and frankly it can be unconstructive to making sound long-term investment decisions. We have focused our efforts in recent days and weeks on meeting with or speaking to the underlying fund managers in the portfolios, as opposed to simply relying on BBC news, to get a better understanding of how the current global backdrop is impacting holdings.

At a market level we witnessed big moves in oil markets with the US banning Russian oil imports and the UK stating that they would phase out of Russian oil by year end. At one point on Tuesday, we saw Brent Crude momentarily touch $139 a barrel before falling heavily on Wednesday and is now currently at around $112 a barrel. Prices at the petrol pumps hit all-time highs this week and this will act as a pinch to the consumer. The higher prices are in effect a windfall for the UK government given the level of fuel duties. It will be interesting to see if there are any reductions to these duties to support consumers.

Gold was once again an asset in demand this week as prices rose through $2,000 an ounce on geopolitical and inflationary fears. At times it can be a frustrating asset to hold, but we continue to see the merits in holding this real asset that offers good portfolio diversification and has returned circa 10% this calendar year.

It was not all doom and gloom in equity markets this week. On Wednesday European equities were in favour with the German equity index rising a staggering 7.9% in a day. The UK and wider global equities all participated in this relief rally too, which appeared to be driven in part by the rumours that Zelensky may be willing to agree to certain Russian demands. It’s a reminder of how quickly things can change and highlights the risk of being out of markets. Positive UK data, which showed the economy emerged strongly from the Omicron variant in January, boosted UK equities on Friday; the FTSE 250 index is now on course for its best week in a year, albeit after falling heavily last week. The strong data may encourage the Bank of England to once again raise interest rates when they meet next week.

US inflation came in at a new 40 year high of 7.9% on Thursday, which was in line with consensus. The expectation is that inflation will continue to rise in the coming months as rising oil and commodity prices feed into the data. With the US Fed also meeting next week, many are expecting to see their first interest rate rise of this current cycle.

As mentioned in the first paragraph we have been meeting with a lot of fund managers recently and will continue to over the coming weeks. There were some interesting takeaways; a global equity manager said that their portfolio was flagging the highest upside to fair-value since August 2020. A UK equity fund manager said that they had personally invested in their own fund this week, acknowledging that they didn’t know if this was the bottom, but it provided a good entry point on a medium-term time horizon. We were also reminded of the embedded inflation protection built into some of our infrastructure and real asset holdings. We will continue to carry out this exercise and focus on making sure we are partnered with talented fund managers and diversify across asset class, investment style and geography.

Andy Triggs | Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors.

The Week In Markets – 26 February – 4 March

This has been another tough week on a humanitarian front, and we want to continue to extend our thoughts and best wishes to everyone impacted by the Ukraine crisis. The purpose of the weekly note, as always, is to report on financial markets, which too have endured a difficult end to the week.

This week has seen heightened volatility across most asset classes as markets attempt to price in a prolonged Russian invasion and the associated risks this would create. As Simon Evan-Cook alluded to in yesterday’s monthly note, uncertainty is something that markets dislike, and uncertainty has increased over the last few trading days.

Safe-haven assets have generally rallied this week, albeit, with bumps along the way. At the start of the week, we witnessed significant falls in developed government bond yields (prices rise). The likely driver of this is the expectation of slower economic growth, which could deter central banks’ from raising interest rates at an aggressive pace. However, it is still likely that the US Fed will raise interest rates by 0.25% this month. Fed chair, Jay Powell, spoke to the House of Financial Services Committee and clearly showed his support for a modest interest rate rise in March to help curb inflation, while acknowledging it was too early to determine the economic impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

While government bonds and gold responded to the escalating conflict by rallying, equity markets hit more turbulent times, with big falls on Thursday and Friday (at the time of writing). French president, Macron, spoke with Putin for 90 minutes, with little success and it became clear a resolution was not close and there could be worse to come. While the sell-off has been broad-based, European equities have generally fared worse than US equities, which is a clear reversal from the trend in January and February this year.

The commodities sector looks poised to finish the week with its biggest weekly gain since the 1960’s. Brent crude oil briefly touched $119 a barrel this week, the highest level since May 2012. European and British gas prices pushed higher with the benchmark Dutch gas price hitting new all-time highs. Rising oil and gas prices will hit the consumer hard which will be a drag on economic growth and is something we need to pay attention to. Consumer balance sheets are generally robust given the ability of many to deleverage and save during COVID-induced lockdowns, however, higher energy prices could see this trend reverse. It wasn’t just oil and gas rising this week, copper hit a new all-time high while wheat prices have risen nearly 75% in 2022. Ukraine and Russia are two of the major exporters of wheat globally and their supply is likely to fall significantly.

As is customary for the first Friday of the month, US Non-Farm Payroll data was released. This is normally a key focus of the market; however, it has been left in the shadows by the geopolitical concerns. The data was very strong, showing 678,000 jobs had been added to the economy against the consensus of 400,000 and the unemployment rate fell to 3.8%. These numbers highlight the underlying strength of the US economy at present and will likely encourage the US Fed to raise rates later in March.

The backdrop of a Russia war makes it uncomfortable to be invested currently and will stir up a range of emotions for investors. While the cause of the concern is different this time, many of the emotions people are feeling will be similar to the initial COVID-19 crisis in March 2020, a period where uncertainty engulfed markets and assets sold off indiscriminately. With hindsight this was the opportune moment to actually be increasing risk. While we don’t want to take undue risks in portfolios, it can be helpful to look back to other crisis moments in history.

Andy Triggs | Head of Investments, Raymond James, Barbican

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors.

The Month In Markets – February

The Month In Markets - February 2022

February will be remembered as a historic month, sadly for all the wrong reasons. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia towards the month end has severe implications, providing an uncomfortable reminder of the events that preceded the second world war. With lives at stake, it feels trite to write about finance right now, but that’s the purpose of this note, so I’ll run through some of the things that happened to markets over the month.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” Niels Bohr, Nobel

I was pleased to be able to meet many of you earlier in February, albeit only virtually. I was even more pleased to hear Andy Triggs, Head of Investments at Raymond James, Barbican, say he wasn’t going to make any predictions about how the then-tense stand-off on the Ukrainian border would play out.

At the time, there were many grand, serious-sounding geopolitical strategists confidently claiming that Putin was bluffing. They are now busy washing their faces, while Andy’s remains reassuringly egg-free.

That’s one good reason not to make such predictions, and particularly not to invest off the back of them. Life is complex; things that shouldn’t happen frequently do. But he also set out another reason: Even if you’re right, markets often do the exact opposite to what you’d expect.

I talked about this in the December note: How markets can appear psychopathic, sometimes reacting positively to bad news. Those of you on the call will remember we ran through some geo-political events from the past, showing how the markets’ shock can be surprisingly short-lived. The instance that stands out for me, because I remember it well, was the day the second Gulf War began in 2003. Having fallen more-or-less constantly following the tech burst in 2000 and then the 9-11 attacks, markets actually rose that day, marking the start of a bull market (i.e. rising prices) that lasted four years.

And so it was in February. As you can see from the chart, European markets sold off on the 24th February, the first day of the invasion, but US markets rose and, by Monday, European markets were back where they started. It’s hard to know for certain why this happens, only to say that markets hate uncertainty (which is why they had been steadily falling for weeks) and Putin’s actions – unfortunately – ended any uncertainty about whether Russia would invade.

That’s not to say markets won’t yet begin to fall again. They’ve remained volatile into March, and no doubt will do so for some time to come. (Predicting that “markets will be volatile” is one of the few safe predictions in investing, which is why so many of us commentators predict it. It’s like telling people to “expect weather”). We’ve simply traded one uncertainty; will Russia invade Ukraine? for others; will Russia invade a NATO country? So this is very far from an all-clear on the investing front.

Another theme we’ve expounded on at length is inflation and its likely impact on interest rates. This is so important for your finances; almost everything else is noise, which is why we spend so much time on it. So in last month’s note we covered the rotation within markets: How everything that had performed well for the last ten years – when inflation was falling – had started to do badly, while everything that had done badly had started to perform well. And all because of inflation’s comeback tour.

Well, it’s all started to rotate back the other way again. And it’s due to what’s happening in Ukraine. You can see in the chart that government bonds (called gilts in the UK, and Treasuries in the US), which hate inflation, continued to fall in the first two weeks of February, but as invasion concerns mounted, they started to rally.

Partly this is because investors use these bonds as financial safe havens in times of stress, often selling riskier assets, like shares, in order to buy them. This pushes the prices of bonds up, and shares downwards.

But it’s also because investors are concerned that the war in Ukraine might lead to a slowing of economic activity, which means central banks are now less likely to raise interest rates to put the brakes on. This too is positive for bonds, but potentially bad news for shares.

Although, as always, it’s never quite as simple as that. Shares don’t like the fact that war might slow the economy, but they do like Central Banks’ responses. But what it has meant so far is that many of the parts of the stock market that had collapsed in January, most notably technology shares, have sprung back to life again. While some areas that had rallied, like European banks, have slumped. The rotation, in other words, is rotating.

But even that’s not that simple. Energy prices, which performed well in January, performed well in February too. So that part of the initial rotation continues. This is due to the threat of a cut in supply from Russia. This too then plays back into the inflation story, as higher energy costs feed into rising prices too. This potentially puts us on a path to stagflation – a grim combination of slowing economic growth and higher inflation. Hardly any assets like this scenario, and may explain why the rally in bond prices was somewhat muted given the severity of the news.

One set of assets that has, unsurprisingly, been walloped are Russian shares, bonds and the rouble. Sanctions, primarily those stopping Russia’s central bank from selling its piles of dollars and euros, have caused the rouble to collapse. Thankfully your portfolios have precious little exposure to anything Russian, so the direct effect of this to you is negligible.

Finally, as you can see from the chart, gold has been a useful investment for us this month. Gold can be a capricious beast. We hold it as insurance, but, like many insurance contracts, you can never be quite sure what it’ll pay out on until after the event. Thankfully, this event seems to be covered, and its rising price has helped your portfolio to weather this storm.

All this paints a highly confusing picture. We do not know how these events will play out – nobody does, and you should treat with caution anyone who claims they do. It’s no time for glib “I’m-sure-it’ll-all-be-fine” statements either – we’re as concerned about the world as I’m sure you are.

In the face of this, and in respect of your capital, we believe balance and diversification are the best options. Placing your assets into a single asset or market based on a prediction risks too much if that prediction proves wrong. And as events have shown, trying to predict the actions of a man like Putin is likely to end badly.

Simon Evan-Cook

(On Behalf of Raymond James, Barbican)

Risk warning: With investing, your capital is at risk. Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. This article is intended for informational purposes only and no action should be taken or refrained from being taken as a consequence without consulting a suitably qualified and regulated person.

Citizen of the World

Events in Eastern Europe over the last week have correctly dominated TV, radio, newspaper and online news. It also meant that almost all equity or bond investors made losses during February, many for the second consecutive month unless – like the U.K. equity market – there was high proportional exposure to commodity sector shares.