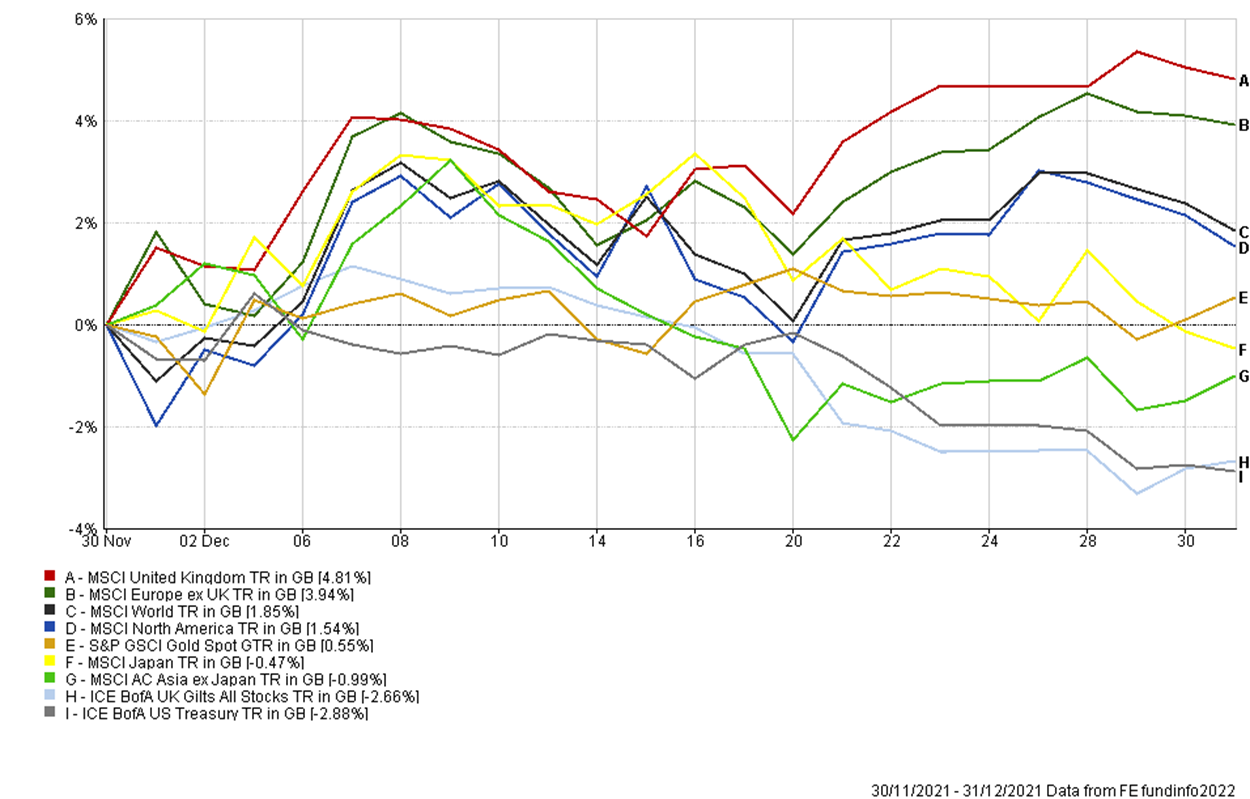

The Month In Markets - December 2021

December is often a good month for stock markets, with the so-called Santa Rally delivering presents to shareholders the world over. However, Asian shares must have made the naughty list this time, as another month of losses capped a poor year for these markets. But western markets took part, as investors looked beyond the Omicron fears that wobbled markets late in November.

This extended a puzzling theme we’ve seen for the whole of last year. Few will remember 2021 positively, as the flow of news has felt relentlessly grim. And yet most stock markets have risen: The UK market is up by almost 20% over the last 12 months; while the global average, driven by a heavy weighting in runaway US shares, made 23% (its third straight year of double-digit returns). How can this be?

This being the complex world of financial markets, there’s no simple answer to that. Instead, there are several answers. And any one of them, or some of them, or all of them, may be true.

One aspect of markets’ behaviour that befuddles investors is that they often react to future events, not to events that have just happened. This makes them seem psychopathic: Bad news hits the papers, perhaps confirming we’re in a nasty recession, then markets rise – apparently rubbing their hands in glee, like a pre-spirits Ebenezer Scrooge.

But what they’re actually doing is reacting to the likely reaction to that news. Most probably that this bad news means future good news: That central banks will, in response, put their foot on the monetary accelerator, which will lead to higher profits and growth further down the line. What can make this especially tricky is that sometimes markets react to the perceived reaction to the likely reaction to that news – and so on – often many times removed. This can make the whole experience like working in a Christopher Nolan movie.

So, one explanation for the weirdly cheerful tone of stock markets is that they’re looking beyond the bleakness, to some future sunlit upland. Perhaps – dare we dream it – a time when COVID is, if not gone, then relegated to the status of seasonal flu. This makes the stock market seem less like a psychopath, and more like a relentlessly cheery doctor. Which, if nothing else, is at least a nicer simile to contemplate so early in your new year.

Under this scenario, markets aren’t nuts. They’re correctly anticipating that companies will continue to do well in the future. Particularly that America’s tech giants will carry on hoovering up market share. These companies have, for the most part, had a cracking 2021 and, given their enormous size and influence on the global stock market, they account for a significant part of those gains.

Another popular explanation for the incongruously good performance is that, in contrast to the first explanation, investors have lost their marbles. Maybe lockdown has caused collectively delusional behaviour, driving us into a bubble the likes of which we last saw in 1999. Backers of this explanation present several exhibits, including historically high valuations, the mania for cryptocurrencies, and bizarre market shenanigans like last year’s GameStop episode. None of these are easily dismissed.

A third explanation – that’s not unrelated to the first two – is that it’s all down to the actions of central banks. For years they’ve been creating money and using it to buy financial assets, all in the hope that it will keep the economy rolling. And, in their defence, that’s essentially what the economy has done, albeit perhaps not as emphatically and evenly as many would have liked.

They took this to another level in response to the pandemic, creating trillions, then trying to inject it into the real world by buying financial assets. Actions like this led to fears of runaway inflation after the financial crisis of 2008 and are causing similar angst today.

But, as one theory goes, perhaps that money is failing to make it into the real world and is, instead, snagged in the not-quite-real world of financial markets. This would explain why real-world inflation hasn’t materialised, but in the financial world of shares, bonds and property, we’ve seen prices inflate dramatically.

And that brings us back to last month. A month in which not only did we see share-price inflation, but also faster real-world inflation, and at a far higher level than we’ve been used to over the last ten years. It was also, not coincidentally, a month in which the strongest sections of the market were those that had been the weakest over that same ten-year period.

I’ll put this another way: Many of the last decade’s winners were the losers in December, and that was due to concerns over rising inflation. Given the margin of their previous victory, that hardly matters. But if it’s a small victory that’s repeated, month after month, over the next decade, then a portfolio built solely of previous winners will perform poorly (just as a portfolio of last decade’s losers will if it isn’t).

This is the conundrum we wrestle with as we position your portfolio. We don’t try to precisely predict which way the world will turn – that’s a fool’s errand. Instead, we try to remain balanced, and therefore less vulnerable to a one-sided view proving the wrong one. In investing as in life, it’s best to focus first on survival, and that remains our priority with your capital.

Simon Evan-Cook

(On Behalf of Raymond James Barbican)

Risk warning: Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors. Raymond James Investment Services Ltd nor any connect company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon any information contained in this article. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.