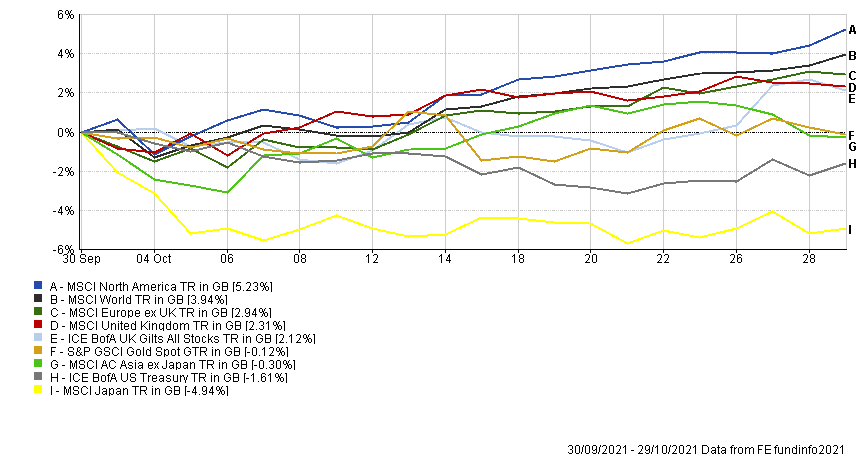

October can be a stormy month for markets, but not this year: Global equities strolled to a 4% return in a calm and orderly fashion. In the absence of headline-grabbing tempests to describe then, I’ll instead use the month’s movements to set out one of the two key debates that currently vex us as we discuss and shape your portfolio.

If those two debates had titles, they’d be: “Stock Markets: Take the Money and Run?”; and “Inflation Vs Deflation”.

We’ll look at the first this month. Stock markets have had a cracking October, that much is clear. Making 4% while your bank account pays nothing is a great result. And it’s not just this month. So far in 2021 global markets have made nearly 20%. Extend that to two years, to now include the worst global pandemic since the Spanish Flu of 1918, the same markets have returned a head-scratching 38%. While if you’d invested ten years back (no mean feat, as back then the world was fretting over the eurozone crisis), you’d be sitting on a return of 261% today.

These are exciting numbers. But we’ve all been around too long, and been to too many parties, to assume we can enjoy that much gain without real-life dishing out some pain to balance things out. In investing terms, this instinctively makes us want to take profits and (in theory) reduce risk by cutting your exposure to equities, and adding more to defensive assets, such as cash or bonds.

And yet we haven’t. Not yet, anyway. We’ve actually been having the exact same debate for the entire (admittedly short) life of the branch; for all that time markets have been sat atop incredible gains (albeit marginally less incredible than today’s). But we decided, thankfully, to stay put. Why?

I think it helps to compare how different this decision is today to 15 years ago. If you’d have had this uneasy, vertiginous feeling at the tail end of 2006, you would still have faced a tricky choice, but then the only cost of running to cash was the cost of a missed opportunity.

The world has changed: in 2006 there were decent, obvious, and risk-free alternatives to shares – most obviously cash (Icelandic banks aside). If you’d have sold your equities and kept the cash, you still would have earned interest of around 5% (unimaginable today, but that was the UK’s base rate as 2006 ended). At the same time, the UK’s inflation rate (CPI) was only 1.6%. So, very roughly, even if equities continued to rise (which, for at least another six months, they did), your wealth would, based on those numbers, still grow by about 3.4% per year (interest less inflation).

Now compare that to today. The base rate is 0.1%, which is basically nothing. So that decision to switch to cash, had you made it last month, would have meant you missing out on the equivalent of 40 years of interest, which is what global equities made in October.

Furthermore, the latest CPI number was 2.9%. So you can assume that, instead of growing, your cash-based wealth has actually shrunk by about 2.8% over the last year (interest less inflation again). And, as long as inflation remains higher than interest rates, it will continue to shrink too. Just as it would have done for the lion’s share of the last 13 years, during which time inflation was persistently higher than interest rates.

This is why we don’t take this decision lightly. Much as our conservative instincts make us cautious after a long rally, we’re also wary that putting you into cash today could be a trap: that we’d be condemning you to an uncomfortable spell on the sidelines, watching as the spending power of that cash ebbs while the value of other assets – that you no longer hold – rises.

Against this, however, is the truth that, much as we think equities are the best place to invest over the long term, they offer no guarantee, much less comfort, that they won’t stumble along the way.

2020 illustrated this rock-and-a-hard-place problem neatly. Take yourself back to the start of that pandemic-ridden year. If two advisers had approached you, one predicting markets would crash by more than 25% within the next 12 months, while the other forecasts a total return of +12% for the year; which one should you have gone with?

Well, they were both right: markets plummeted by 26% in March as lockdowns took hold, but by the end of the year they had more than recovered, finishing with a return of 12%. (The actual answer to that question, though, is you shouldn’t have chosen either of them: if any adviser tells you precisely what the next year will hold, you should run like the wind. But that’s another story.)

That, in a nutshell, is the conundrum we face today. We all agree that – over the long term – equities offer not just the best opportunity to beat inflation, but to actually grow the spending power of your wealth too. But, in the short term, they are susceptible to lurching and entirely unpredictable drops in price, which will put you through the emotional wringer (something we are obviously keen for you to avoid).

But we can also all see that, while many of the classical ‘safe-haven’ assets, like cash or bonds, might protect you from massive waves in the short term, over the longer term they put you at serious risk of slowly sinking, as your wealth’s spending power is eaten away by inflation.

It’s our job to balance those considerations, and with them your portfolio. It’s no use us putting you in the best returning investment over the next 10 years if the ride is so unbearably rough that you abandon ship along the way (that’s the last of the nautical metaphors, I promise). In doing our job we consider and balance many factors, such as the valuations of different asset classes and the wider economic and social environment, and then marry those to your own personal need for returns and appetite for risk.

So that’s what we’ll continue to do. After a bumper month like October, you can assume we’re more likely to reduce risk than add to it. But it’s a team decision, and it’s never as simple as “markets have gone up, so sell”. That would be too easy: markets, like life, aren’t that kind.

Simon Evan-Cook

(On Behalf of Raymond James Barbican)

Risk warning: Opinions constitute our judgement as of this date and are subject to change without warning. With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not recover the amount of your initial investment. Certain investments carry a higher degree of risk than others and are, therefore, unsuitable for some investors. Raymond James Investment Services Ltd nor any connect company accepts responsibility for any direct or indirect or consequential loss suffered by you or any other person as a result of your acting, or deciding not to act, in reliance upon any information contained in this article. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.